Understanding Acceptability of eConsent from a Global, Ethical, and Industry Perspective

By Hilde Vanaken, Susie Song, Steve Walker, Sam Thomas, Eric Delente, Steven Johnson, Edwin Cohen, Vinita Navadgi, Radu Antonie, Nora Meskini, Jenna McDonnell, and Valeria Orlova

To date, there is limited insight into the perspectives on eConsent in clinical trials of Independent Ethics Committees/Institutional Review Boards, collectively referred to as Ethics Committees (ECs) in this article, as well as into the opportunities and barriers faced by sponsors (commercial, non-commercial) and vendors (technology companies, CROs). The European Forum for Good Clinical Practice (EFGCP) eConsent initiative, comprised of over 50 companies, has conducted two surveys to gain a comprehensive understanding into behind-the-scenes perspectives of ECs and sponsors/vendors. This article represents the key findings of both surveys and detailed results can be accessed through the supplemental information section.

The importance of the right understanding about eConsent

A correct and aligned understanding of eConsent is crucial to ensure that all stakeholders are on the same page. For this purpose, the EFGCP eConsent initiative has developed a comprehensive glossary of eConsent terms including over 60 harmonized eConsent platform and operational aspects. This resource equips stakeholders with a unified language and the necessary knowledge and terminology.1,2 The glossary was incorporated in the introduction of both surveys.

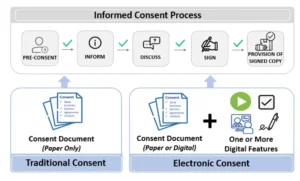

To recap, ‘eConsent’ is an overarching term used to represent the traditional informed consent process, supported by one or more digital features.1,2 A visual representation of this eConsent definition and some examples of digital features are shown in Figure 1. There are many different eConsent models, there is no one-size-fits-all eConsent model. Each study, each indication, each site, and each participant might have its own needs and requirements.

EC eConsent survey: Key highlights

1. EC eConsent survey respondents characteristics

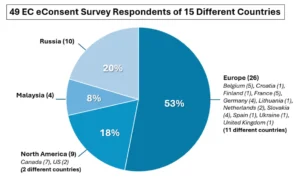

49 EC respondents from 15 different countries completed the EC survey of which 53% were from Europe, and the rest were divided between Russia (20%), North America (18%), and Malaysia (8%), as shown in Figure 2.

The level of experience with eConsent was variable:

- 61% had reviewed and approved/rejected eConsent.

- 35% had never been asked to approve eConsent

- 4% had no opinion

A substantial proportion of ECs respondents had previously been asked to approve eConsent in North America (78%), in Malaysia (75%), and in Europe (65%). In contrast, only 30% of Russian EC respondents have been asked to approve eConsent.

2. Preserving human Interaction with eConsent: The most important factor for ECs

The most important driving factor for EC respondents (43%) to approve eConsent was preserving the interaction between investigator and participant.

Participant-investigator interaction is a foundational Good Clinical Practice (GCP) of informed consent.3 In addition, while some Health Authority guidelines (e.g. EMA) recommend a physical interaction, a remote interaction can also be justified in some cases, opening alternative modalities for this investigator-participant interaction.4

EC respondents further scored patient-centricity (22%) and regulatory acceptance (18%) as important driving factors to approve eConsent. Of relatively smaller relevance for EC respondents was the knowledge that eConsent is accounted for in site guidance documents (2%), that there is an easy access to technology, training and documentation (2%), and that it enables decentralized trials (2%).

3. eSignatures acceptability by ECs: Various factors play a role

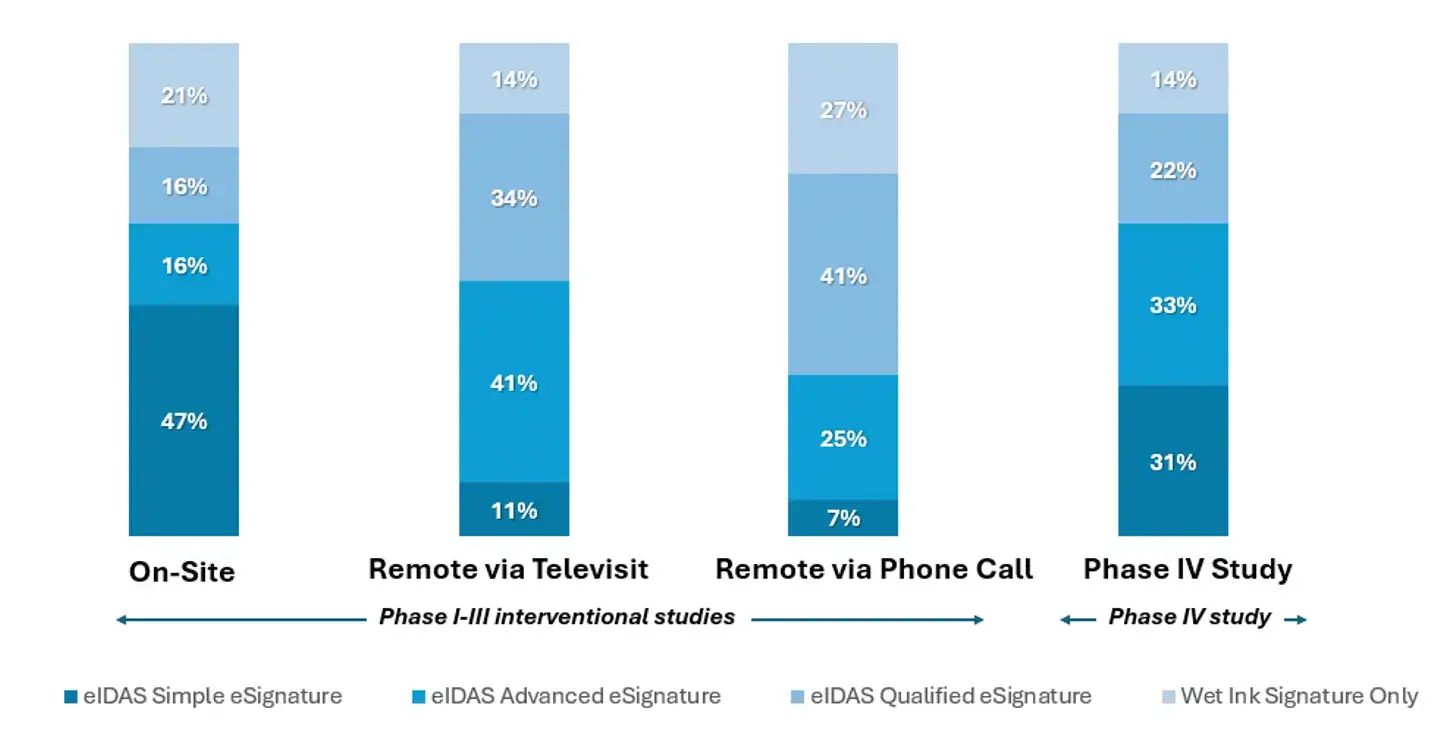

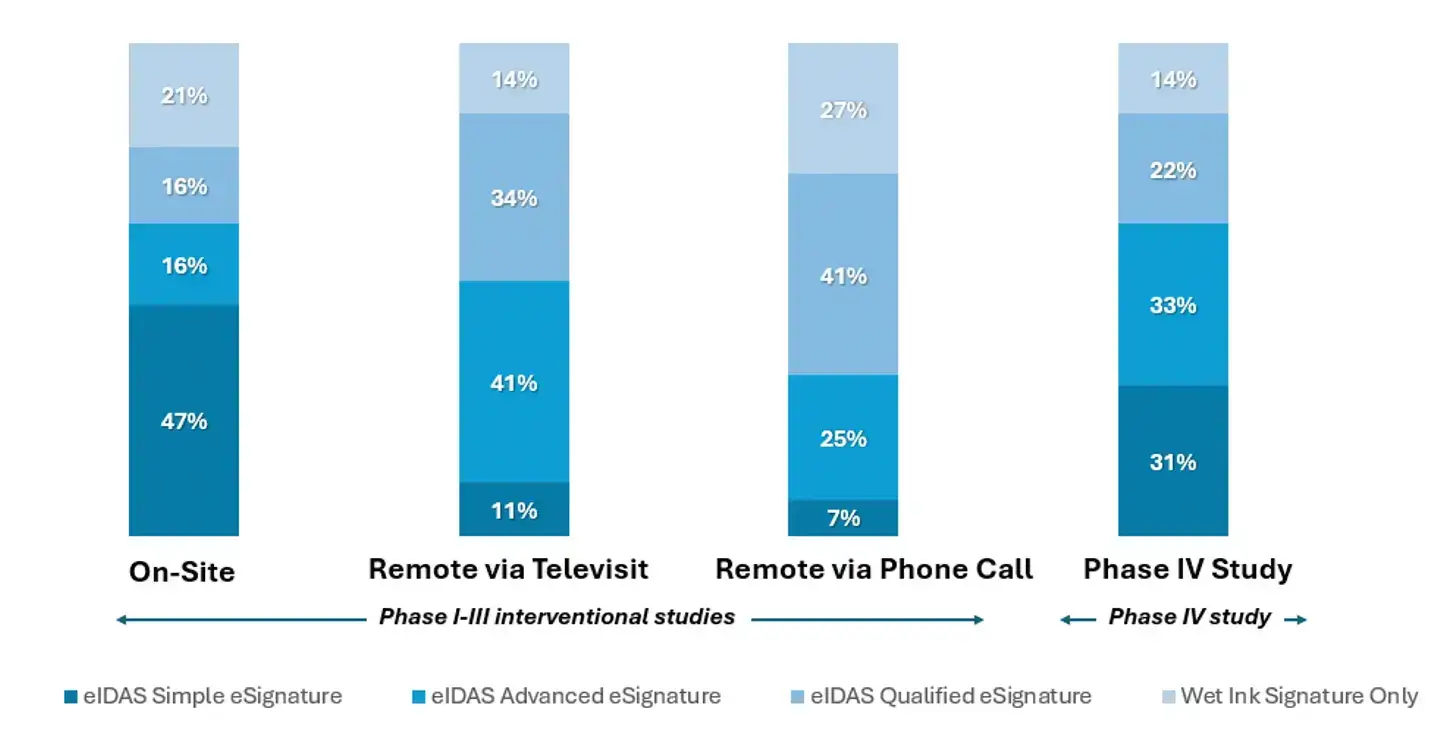

The interpretation of eSignature terminology varies greatly across the globe. A handwritten signature drawn by finger or stylus on an electronic device is considered an eSignature according to European eIDAS regulations, but NOT according to FDA regulations. Hence, we recommend describing the signature process in detail to ensure it is clear for all stakeholders.1,2 In the surveys, we used the eIDAS eSignature terminologies: Simple eSignature, Advanced eSignature, and Qualified eSignature.5

The EC survey results showed that eSignature requirements became more stringent when moving from on-site workflows to remote workflows conducted via televisit or via phone call.

As illustrated in Figure 3, an eIDAS Simple eSignature was acceptable:

- for Phase I-III interventional studies by

- 47% of EC respondents when eConsent was conducted on-site

- 11% of EC respondents when conducted remotely via televisit

- 7% of EC respondents when conducted remotely via phone call

- for Phase IV studies by

- 31% of EC respondents

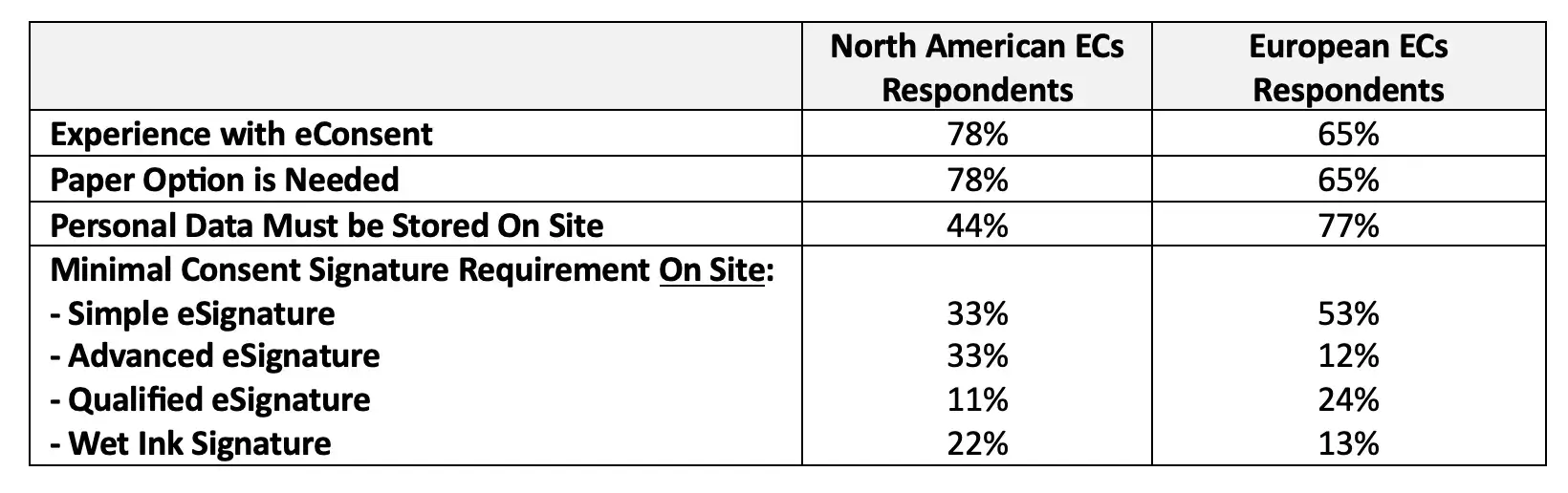

Regional difference existed with an eIDAS Simple eSignature on-site being acceptable by 53% of European EC respondents versus 33% of North American EC respondents, and 13% of European EC respondents requiring a wet-ink signature versus 22% of North American respondents. More details can be accessed through the supplemental information section.

4. Offering both paper and eConsent: A key recommendation of ECs

The EC survey posed a forward-looking question to gauge the sentiment on providing consent only electronically. 61% of EC respondents did not agree with this. North American EC respondents had the highest score (78%), followed by European (65%), and Russian EC respondents (60%). On the contrary, Malaysia seemed to be more supportive for providing consent only electronically with 75% agreement. The emphasis on patient-driven choices and diversity and inclusion without additional biases is presumed to be driving the results. Providing options for participants and sites is important to avoid creating a new diversity barrier for participant populations that lack basic digital literacy skills.6

5. The site: Preferred location to store personal data for ECs

When it comes to data storage and residency requirements, 61% of EC respondents recommended that personal data should be hosted at the investigator site. Regional differences existed with 77% of European EC respondents recommending the on-site hosting of personal data versus 60% of Russian, 44% of North American, and 25% of Malaysian EC respondents.

While EC respondents expressed a preference for on-site hosting, it must be noted that not all sites may have the necessary infrastructure or manpower to support on-site data hosting. Without any doubt, participant data and participant personal data protection falls under the responsibility of the site, but there are also other ways that this can be achieved. For example, by validated, secure and controlled data encryption, data transfer and data access, while maintaining and offering a more harmonized approach and access to eConsent for sites and their participants.

6. Limited impact on monitoring or archival requirements expected by ECs

The majority of the EC respondents indicated that there is no difference in monitoring requirements compared to paper (90%), nor that eConsent archival requirements exceeded GCP requirements (80%). Half of the EC respondents (51%) indicated that they had an ICF guidance document available, of which 60% indicated that no updates were needed to cover the use of eConsent.

Sponsor and vendor eConsent survey: Key highlights

1. Sponsor/vendor eConsent survey respondents characteristics

In total, 42 respondents completed the sponsor/vendor eConsent survey with 67% sponsor and 33% vendor respondents.

The level of experience varied:

- 26% had no eConsent experience

- 36% had piloted eConsent

- 31% implemented eConsent frequently

- 7% used it in all studies

As expected, vendors reported a higher eConsent experience compared to sponsors: 36% of sponsor respondents had no eConsent experience versus 7% of vendor respondents.

2. Compliance and patient-centricity: The most important drivers for sponsors and vendors

90% of sponsor/vendor respondents scored improved compliance and quality of the consent process as the most important factors driving the use of eConsent. That number increases to 96% if we consider only the sponsor representative responses. Patient-centricity was another important factor, scoring 86% across the combined sponsor/vendor group and it was even the number one factor considered by vendors. Other important factors, ranging from 50% to 60%, were enabling decentralized trials, integration with other clinical systems, reduction of dropout, and improvement of recruitment rates.

3. Site adoption and regulatory approval concerns: The most significant barriers for sponsors and vendors

Poor site adoption was considered the most significant barrier by sponsor respondents (61%), whereas vendor respondents noted regulatory approval concerns (43%) as the most important barrier. High cost was ranked as the third significant barrier by both sponsors (36%) and vendors (29%). Lack of organizational delivery structure and process (32%), challenges with an eConsent platform (29%), and delay in timelines (29%) were considered as significant barriers by sponsor respondents but limited or not even seen as a barrier by vendor respondents, as illustrated in Figure 4.

4. Video: A valuable yet underutilized eConsent digital feature by sponsors and vendors

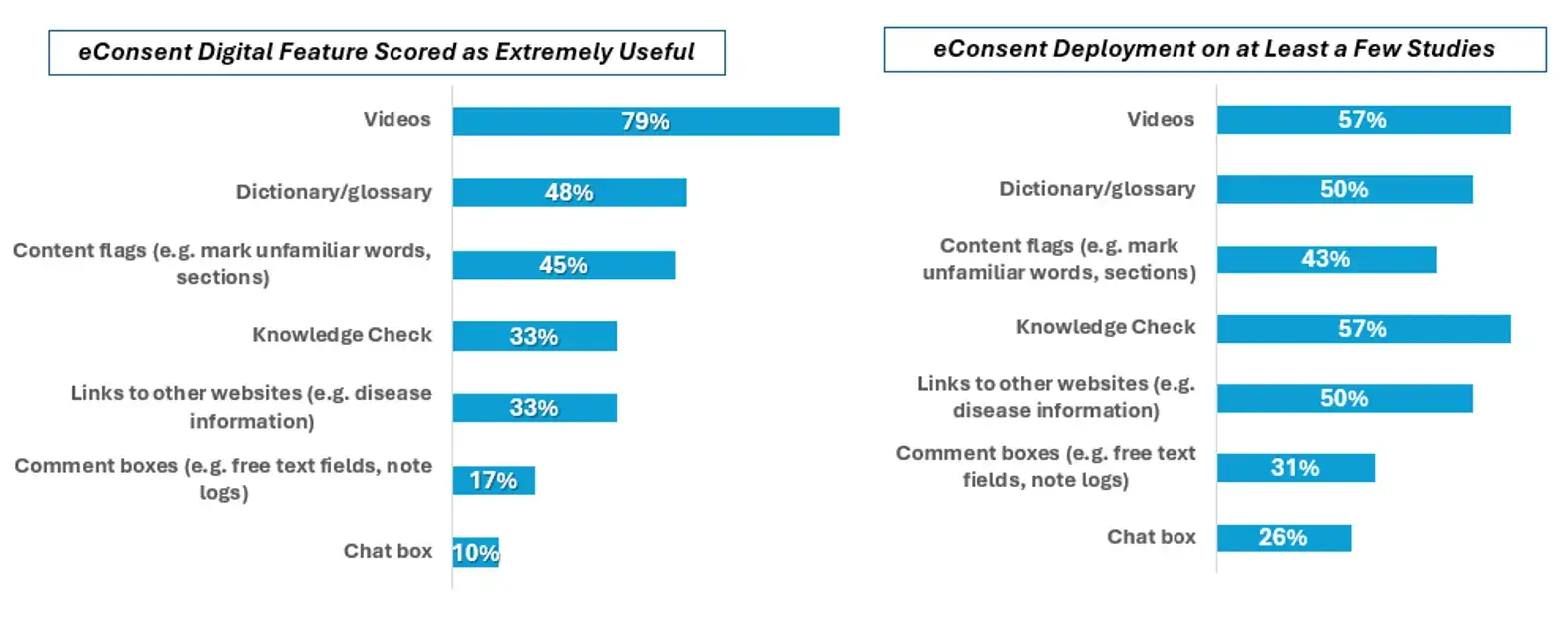

The video digital feature perceived the highest score (79%) by sponsor/vendor respondents on the value matrix of digital features, followed by dictionary/glossary (48%), content flags (45%), knowledge checks (33%), and links to other websites (33%). Comment boxes (17%) and chat boxes (10%) were less frequently rated as extremely useful digital features.

The frequency of deployment of digital features did not necessarily mirror the usefulness perception. As shown in Figure 5, 79% of sponsor/vendor respondents considered the video as extremely useful but only 57% had used it. Similarly, some digital features perceived as less useful (e.g. chat box, comment box) were deployed by ~30% of sponsor/vendor respondents.

5. Live video call with investigator: The most common used remote consent authentication methods

Live video call with investigator (43%), two-factor authentication (33%), and a Qualified Trust Service Provider ID verification (21%) were reported by sponsor/vendor respondents as the most commonly used Participant Authentication Methods for remote eConsent. Exchange of random code in conjunction with a phone call (10%) and CAPTCHA (5%) were less commonly used. A high number of sponsor/vendor respondents (45%) also selected “Other,” which included methods such as signatures collected at the site, or post office verification, as well as some respondents indicating that they had no experience with the topic.

Submission requirements aligned among ECs, sponsors, and vendors

Both EC and sponsor/vendor respondents evaluated the EC submission requirements. System privacy and security documentation (69%), attestation that eConsent content is identical to paper content (55%), system-printed PDF of the document (55%), and screenshots of digitized content (51%) were highest scored by EC respondents, followed by story boards of multimedia content (33%) and access to the eConsent platform (29%). Comparable categorizations were given by sponsor/vendor respondents although they gave a higher score for screenshots of digitized consent (67%) and storyboards of multimedia content (48%).

Conclusion: One step closer towards transparency and clarity

Creating transparency in perspectives by directly inquiring with the involved stakeholders, instead of making assumptions on their behalf, is overall considered the best approach but in practice not so often implemented. The survey results presented in this article directly present the views of ECs, sponsors, and vendors.

What we learned is that, not surprisingly, the most important items for ECs are:

- ensure the participant-investigator interaction is not impacted

- ensure a paper option is available to enable broad inclusiveness

- ensure participant data and identity are securely stored and protected

There were clearly differences between European and North American EC respondents, but some were much less profound or not as expected with some examples shown in Figure 6. More examples and details can be accessed through the supplemental information section.

Similarly, sponsor/vendor survey results showed alignment but also differences, especially when it comes to drivers and barriers. For example, ~30% of sponsor respondents considered challenges with an eConsent platform, delays in timelines, and lack in organization delivery structure and process to be a significant barrier, while this was limited or not seen as a barrier by vendor respondents.

To note, survey results represent only a small fraction of the global community. In addition, to date, there are still many different interpretations and misunderstandings of what eConsent is about, which might have impacted the responses given by the different stakeholders.

The survey results described in this article represent another outcome of the EFGCP eConsent initiative, one of the largest and most collaborative industry efforts in eConsent. Other tools developed are:

- Glossary of eConsent Terms: covering over 60 eConsent platform and operational aspects terminologies, definitions and examples1,2

- eConsent Study Documents Recommendations: covering recommendations for nine different study documents on various eConsent platform and operational aspects7,8

- eConsent Fit-for-Purpose Study Framework: providing a 5-process flow to define and design the right eConsent for a particular study and its stakeholders, and to analyze and generate effective and comparable study data on eConsent9,10

Upfront interactions on eConsent with key stakeholders, such as Ethics Committees, remain also very valuable as previously recommended by the involved stakeholders.11

Key to remember is that there is no one-size-fits-all eConsent model. Each study, each indication, each participant, and each site might have its own requirements. The suite of eConsent tools listed above is publicly available on the EFGCP eConsent website and we hope you will join our journey to bring eConsent to the place it deserves.

Supplemental Information

The detailed results of the ECs eConsent survey and sponsors/vendors eConsent survey are available at the EFGCP eConsent website.

Acknowledgements

This significant work would not have been achievable without the dedication and support of the EFGCP eConsent database workstream team. We would also like to express our gratitude to all the organizations that participated in the online surveys.

About the authors

Hilde Vanaken (EFGCP, TCS) spearheads the EFGCP eConsent Initiative consisting of 6 workstreams. Susie Song (Biogen) is a co-leader of the EFGCP eConsent Database workstream responsible for this article. Steve Walker (CSL Behring), Sam Thomas (ClinOne), Eric Delente (Medidata), Steven Johnson (Takeda), Edwin Cohen (Evinova), Vinita Navadgi (IQVIA), Radu Antonie (Roche), Nora Meskini (Debiopharm), Jenna McDonnell (PPD), and Valeria Orlova (Freelance consultant) are members of the Database Workstream.

References

- eConsent: Why Language Matters! Applied Clinical Trials, 20 December 2023. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/econsent-why-language-matters

Glossary of eConsent Terms. EFGCP eConsent website, 5 July 2024. - Glossary of eConsent Terms. EFGCP eConsent website, 5 July 2024. https://efgcp.eu/public/EFGCP%20Glossary%20of%20eConsent%20Terms.pdf

- ICH Harmonized Guideline, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) E6(R3), Draft version 19 May 2023. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_E6%28R3%29_DraftGuideline_2023_0519.pdf

- HMA, EC & EMA, Recommendation Paper on Decentralized Elements in Clinical Trials, Version 1, 13 December 2022. https://health.ec.europa.eu/latest-updates/recommendation-paper-decentralised-elements-clinical-trials-2022-12-14_en

- EU Regulation on Electronic Identification and Trust Services for Electronic Transactions in the Internal Market (eIDAS), July 2014. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2014.257.01.0073.01.ENG

- Digital literacy in the EU: An overview. 6 December 2023. https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/digital-literacy-eu-overview

- Navigating eConsent Submissions: Who, What, Where and Why? Applied Clinical Trials, 10 November 2023. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/navigating-econsent-submissions-who-what-where-and-why-

- eConsent Study Documents Recommendations. EFGCP eConsent website, 5 July 2024. https://efgcp.eu/public/eConsent%20Study%20Documents%20Recommendations.pdf

- Effective eConsent Strategies for Every Study: Utilizing the eConsent Fit-for-Purpose Study Framework. Applied Clinical Trials, 12 August 2024. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/effective-econsent-strategies-fit-for-purpose-study-framework

- eConsent Fit-for-Purpose Study Framework. EFGCP eConsent website, 12 August 2024. https://efgcp.eu/public/eConsent%20Fit%20For%20Purpose%20Framework.pdf

- Awareness and Collaboration across Stakeholder Groups Important for eConsent Achieving Value-Driven Adoption. Therapeutic Innovative Regulatory Science, 18 July 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2168479019861924